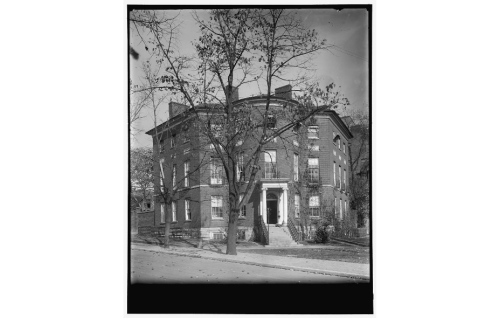

The Georgian style Sylvester Manor House, built in 1737.

Sylvester Manor is a developer’s dream. The approximately 250-acre estate of woods, water, and fields is located on Shelter Island, a wealthy enclave just a quarter mile ferry ride from the Hamptons and 100 miles to the east of Manhattan. There is no telling how many millions the property could have fetched in 2006 when its then owner, Alice Fiske, died at 88. Thankfully the two men who inherited the manor, Eben Fiske Ostby and his nephew Bennett Konesni, had a bigger vision for the place.

In 1653, Nathaniel Sylvester and his teenage wife, Grizzell, moved to Shelter Island after buying it from the Manhansett Indians. Nathaniel needed a place to support the family Caribbean sugar operation. Grizzell needed to get away from the endless taunting over her name. The desolate 8,000-acre island fit the bill.

The South is chastised for its role in perpetuating the scourge of slavery in early American history–and for good reason. The vast majority of slaves lived south of the Mason Dixon Line. But the North was by no means innocent. And of the northern states, New York had more slaves than any other.

The about 20 slaves at Sylvester Manor made it one of the largest of its kind in the region. Those Africans–along with indentured servants and local Indians–provided the labor for a plantation that produced livestock, horses, and barrels. Slaves lived on the property for nearly 200 more years; the last Sylvester Manor slave was freed in 1821, just six years before New York State banned slavery and 42 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Today the only clue to their existence at Sylvester Manor is a plot of land marked by a rock that reads: Burying Ground of the Colored People of the Manor From 1651. The grave markers are long gone–if they existed at all–but an estimated 200 bodies are interred there.

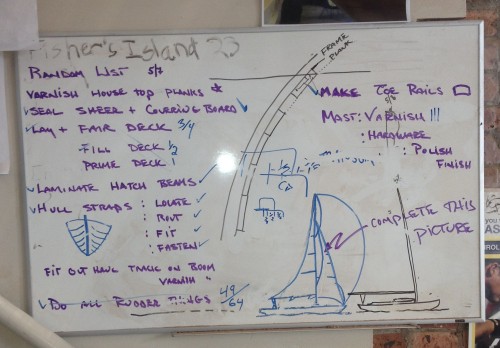

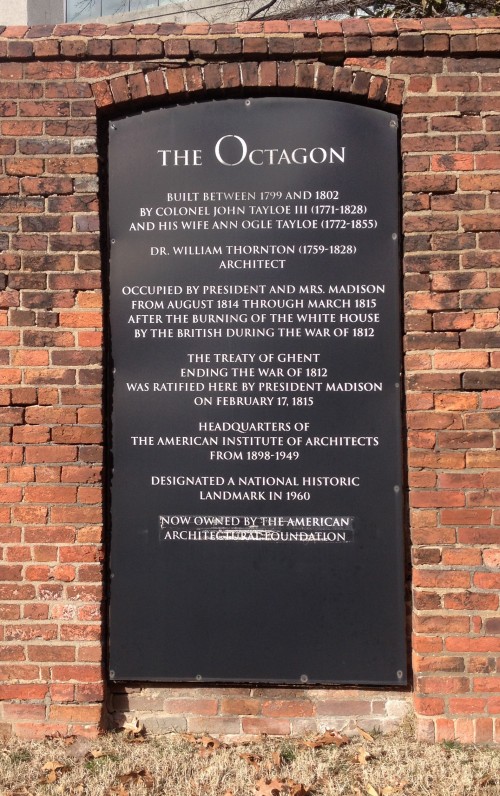

Once Nathaniel and Grizzell died, their son Giles, by all accounts a louse, sold off half the acreage to live la vida loca in Boston’s drinking holes and gambling dens. Giles was badly in debt by the time he died, and the estate was nearly lost to his creditors upon his death. Nathaniel and Grizzell’s grandson Brinley Sylvester fought in the courts to regain 1,000 acres and is responsible for the circa 1737 Georgian mansion that still stands today near Gardiners Creek.

Just before the Civil War, Sylvester Manor transitioned to a summer retreat under the ownership of Harvard professor Eben Norton Horsford. He married into the estate-holding family and must have liked the manor a lot, because after his wife died he married her sister. Horsford, who invented baking powder, invited some of his Harvard pals for stays. One of the friends was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who wrote a recently discovered poem to commemorate a Horsford birthday.

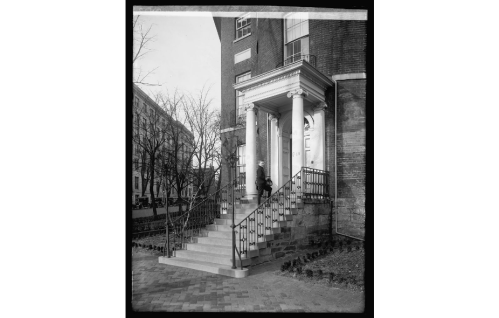

Horsford’s daughter Cornelia inherited the property in 1903 and embarked on an improvements campaign. She hired Lincoln Memorial designer Henry Bacon to design the Colonial Revival style addition to the manor house. Bacon also added porches and tweaked the interior layout. Cornelia’s overhaul included the redesign of the gardens.

Pixar co-founder Eben Fiske Ostby became the 10th generation owner of the estate after Alice Fiske’s 2006 death. He was not interested in assuming the throne of the mini kingdom, but he didn’t want to sell and break the family’s continuous 350-year chain of ownership either. So in 2011, Ostby teamed up with his nephew and 11th generation owner, Ostby Bennett Konesni, to found the nonprofit Sylvester Manor Educational Farm.

As a result a large chunk of the estate has been protected by conservation easements. Not only does the setup prevent the land from development, it also returns 83 acres to their agricultural roots. But instead of slaves and indentured servants growing food for subsistence, it’s recent college grads growing organic crops for island restaurants. The farm has become such a point of local pride that the eateries base their menus around what foodstuffs are in season at the farm. Meanwhile, a farm stand on the property sells fresh produce to the general public.

The new ownership team also has also opened up Sylvester Manor to the public with cultural events, dinners, school programs, and tours of the Manor House. (It was through the monthly summer Saturday tours that I was able to visit the property on July 18, 2015.) And before Alice Fiske died, she endowed the Andrew Fiske Memorial Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts to support digs on the property to continue to tell the story of Sylvester Manor’s deep history.

For more information

Landscape historian Mac Griswold’s book “The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island” is a well researched account of Sylvester Manor’s early history.

Many articles have been written about Sylvester Manor’s recent transformation.

This original paneling in the east parlor has received two coats of paint: the original blue poking through from 1700s and a second in the 1800s.

The French tropical wallpaper in the west parlor dates to the 1880s.

View from the back porch.

This 17th century English cannon, found buried near the manor house in the 1950s, reportedly was hidden from the Dutch during the 3rd Dutch-Anglo War.

A canoe rests along the banks of Gardiners Creek.