I presented on this topic at the 2014 Society for Commercial Archeology conference in St. Petersburg. Click here to watch my presentation.

The starting box doors flip up, and the greyhounds burst toward the rail where the remote-controlled lure–a white fake rabbit appropriately named Hareson–zips around the turn. The dogs gallop full speed in pursuit around the dirt oval, which measures 1,320 feet long and 21 feet wide. They complete about a lap and a half before Hareson is halted and jerked out of the dogs’ reach just before they catch up to it. They stop running and seem disappointed, but their mood buoys at the sight of their handlers, who come onto the track to corral the dogs and return them to the paddock. This scene has been repeated thousands of times in Derby Lane’s 89-year history, but it’s unknown how many more times it will be repeated at the landmark, considered the oldest of its kind in continuous operation.

Greyhound racing is called the sport of queens, but it’s more like the sport of queens’ servants. It traces its roots to the 17th century English pastime of coursing, in which two greyhounds chase after a rabbit. Greyhounds can reach speeds of 45 mph, so they were well bred for the game. A coursing judge scrutinized the hounds not for how fast they killed the rabbit, but by the amount of athleticism they exhibited in the process.

Americans sometimes offered their own take on coursing. For example, in Kansas and other Great Plains states, it was practiced more to eradicate jackrabbits and coyotes than for sport. Owen Patrick Smith is credited with pioneering modern greyhound racing when he invented the mechanical lure in 1909. Greyhounds, Smith proved, would chase anything–even if it wasn’t alive. The first greyhound track opened in Emeryville, California, in 1919, and the pastime spread across the country.

Dog tracks were particularly popular in Florida, which was undergoing rapid development at the time. Promoters played up Florida as an Eden where all life’s fancies could be enjoyed. They billed dog racing as a classy affair on par with thoroughbred horse racing. But racegoers were not Vanderbilts, Astors, or Rockefellers; they were working-class, hence why dog races were held at night and why admission was much cheaper than the horse track. Associations with mobsters like Al Capone gave dog racing a shady reputation.

Derby Lane was a product of greyhound racing’s initial swell in popularity. It was established in 1923 when a group of businessmen bought acreage northwest of St. Petersburg along Gandy Boulevard from lumberman T.L. Weaver and his brother-in-law John Loughridge. The pine scrub land was desolate, but it was near the recently completed Gandy Bridge, the first to link Tampa and St. Pete via automobile.

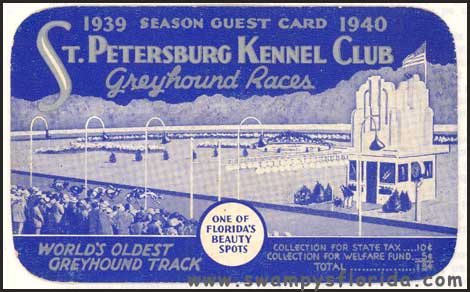

The consortium had a sand track, grandstand, and clubhouse built. But the group took a financial hit, and the property reverted back to Weaver when they couldn’t pay their bills. It has remained in the family since. The first dogs raced at what was known as the St. Petersburg Kennel Club before a crowd of 4,000 people on January 3, 1925.

Those early years were wild. Cars sometimes dashed around the track. When there was dog racing, monkeys dressed as jockeys rode on the backs of the greyhounds. Neither animal enjoyed the experience, because the monkeys were known to freak out and bite the greyhounds. Betting wasn’t legal, so the proprietors got around it by selling shares in the dogs. Even losing tickets returned a nickel.

Florida legalized parimutuel wagering in 1931, and Derby Lane flourished. There were a few down years during World War II when racing was banned. Then a season was lost when a few years after the war when the dog owners went on strike. But, for the most part, Derby Lane was consistently a top attraction in the region. Regarded as the Churchill Downs of dog tracks, famous patrons included baseball superstars in the area for spring training such as Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, and–no surprise here–Pete Rose.

Everything changed in 1988 when the Florida Lottery debuted. Up until then, parimutels were the only legal places in the state to bet. But, with the introduction of the lottery, gamblers only had to schlep down to their nearest convenience store to get their fix. Derby Lane’s attendance collapsed. The Weavers slashed costs. Gift shop? Gone. Band and band shell next to the odds board? Gone. In-house bar? Gone. To counter, they expanded the race season from four to six months. They introduced simulcast wagering and broadcast races over the Internet for the first time. They even opened a lottery ticket window at the track. The Weavers also attempted to convert the Plaza Building into a nightclub, but that didn’t work out. The giant edifice now sits mothballed.

Beginning in the late 1970s, reports on greyhound racing deterred potential new fans. Greyhounds aren’t pets that also race. They’re bred, born, and raised do one thing: run. Similar to race horses, they are sometimes euthanized when they can’t run anymore–or don’t run well enough. They live in kennels starkly different from the living situations of most dogs in America. Many are fed meat that the FDA considers unsuitable for human consumption. Greyhound racing opposition groups have brought all this to light. And the mass deaths of greyhounds in kennel fires hasn’t exactly boosted the industry’s image. Even Homer Simpson decried the dog track as “sleazy” in the premiere episode of The Simpsons.

The decline of greyhound racing is a nationwide trend. In 1997, there were 49 dog tracks in 15 states in 1997. Today that number has dwindled to 22 tracks in seven states. Twelve are in Florida.

Yet Derby Lane retains its post-war grandiosity. Separated from Gandy Boulevard by acres of empty parking spaces, the main entrance in the grandstand is located just under the signs that read “GREYHOUND RACING” and “DERBY LANE.” The original wood grandstand was replaced by a larger concrete and steel cantilevered structure in 1949, about the same time the property became known officially as Derby Lane. The grandstand is flanked by a pair of International style clubhouses, enclosed by expansive glass windows. The Plaza Building to the west was built in 1967; the Derby Club in 1976. The manicured grass infield includes a scenic pond with a boardwalk to the island in the middle. The odds board was erected in 1949, and the paddock went up in 1967. The track has been in the same spot since the start, though it has been elevated and banked. The track’s retro feel has not gone unnoticed by Hollywood; Brad Pitt and Rob Reiner filmed scenes for Ocean’s 11 there.

While a big race day might draw a couple thousand people, it is nothing like the pre-lottery days when crowds occasionally eclipsed 10,000 at Derby Lane. On a Saturday afternoon in December, a couple hundred people watched the festivities from the grandstand and blacktopped apron. The mixed bag included leathery old men who smelled like aftershave; pasty senior couples likely visiting from the Midwest; and a grungy man who either had Tourette’s or just enjoyed randomly yelling sounds. Blue-haired old ladies bedecked in pearls stayed away from this menagerie and munched on scallops at dining tables in the air-conditioned clubhouse.

Below them, in the bowels of the clubhouse, the atmosphere was much more serious in Derby Lane’s poker room. The players–mostly men, some of whom donned hats and sunglasses to imitate the highrollers they saw on ESPN–crowded around tables shaped like a race track. They were devoid of emotion as they tossed plastic chips into the pile at the table’s center.

Poker saved Derby Lane. The track introduced cards in 1997, and the move has been profitable. But, to offer poker, the law requires the state’s dog tracks to schedule 90 percent of the numbers of races they ran in 1996, when the rule went into place. Derby Lane holds more races now than ever. It used to only offer a slate during the coldest months, but now it also hosts the meet for Tampa Greyhound Track, which stopped racing in 2007. The Tampa track found a loophole and moved its races to Derby Lane so it could still have on-site poker.

Legislation is currently in the works to decouple the race and poker provision. Greyhound racing is not profitable at most tracks, and they would stop racing if it’s not required. Ironically, both track owners and anti-racing activists support the measure, the former resigned to their fate as poker dens. Dog men, at risk of losing their livelihoods, adamantly oppose. Should the provision pass, Derby Lane intends to keep racing to meet its simulcast demands. How long that will continue is anyone’s guess.

For more information

Gwyneth Anne Thayer wrote a comprehensive book on greyhound racing in the United States titled Going to the Dogs: Greyhound Racing, Animal Activism, and American Popular Culture.

The lure was on the outside of the track in this 1925 photo. Burgert Brothers. University of South Florida Library. http://usf.sobek.ufl.edu/SFS0024140/00001

Babe Ruth eyes the cup for booze while Lou Gehrig is blinded by the camera flash. It must have been bright, because the dog’s trainer is covering the joyousvictor’s eyes.

1938. Check out the Art Deco style building at the finish line. University of South Florida Library. http://usf.sobek.ufl.edu/SFS0010918/00001

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/161640

After the grandstand was built in 1949. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/161641

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/163049

Packed house in 1976. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/59083

Pingback: Five-Year Anniversary | Gator Preservationist

I work at derby for 15 years and my wife most of those years.we have very fond memories of that time.dick hart was mutual manager and many good people we worked with are remembered.

Would anyone remember a Gentlemen that was from Ohio and ran his greyhounds late 1940’s to 1950’s. His wife died and he remarried, but he had

children. One child of his was a daughter, born 1931 and she gave birth to a daughter In 1950 at a home for unwed mothers in St Petersburg, Fl. That child is me and I would LOVE to find someone from my family.

Thank you

Marti

marti44b@hotmail.com