Too often preservationists become so enamored by a building’s architect, they overlook its shortcomings. I fear this is occurring with the two Sarasota High School buildings designed by Modernist architect Paul Rudolph.

Early this month, the Sarasota County School District revealed its plans for the two Rudolph-designed buildings on the SHS campus, and preservationists are not happy. The gym is too small, district officials say, and must be torn down. They don’t want to demolish the classroom building addition, but they do want to gut its rooms and enclose its two-story breezeway and use it as a media center.

The school district employees seeking the renovations at Sarasota High are the same who successfully pushed for the demolition of a deteriorated Riverview High School, another Rudolph project, in 2009. That preservation effort drew international attention as advocates futilely sought to raise money and gain support to rehabilitate the Rudolph buildings and leave enough room on the school’s cramped property for a new campus.

As I wrote about in my thesis, preservationists in the Riverview case invoked Rudolph so often, they turned off many citizens who couldn’t have cared less about the designer–they just wanted a functioning school at a reasonable price. By the time they developed a plan to rehabilitate the buildings, they were too far behind to stop the momentum.

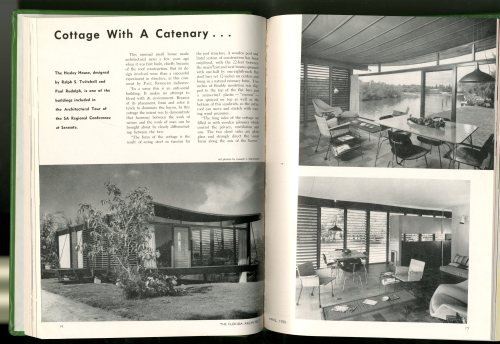

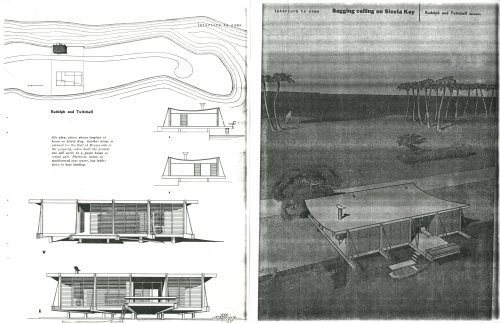

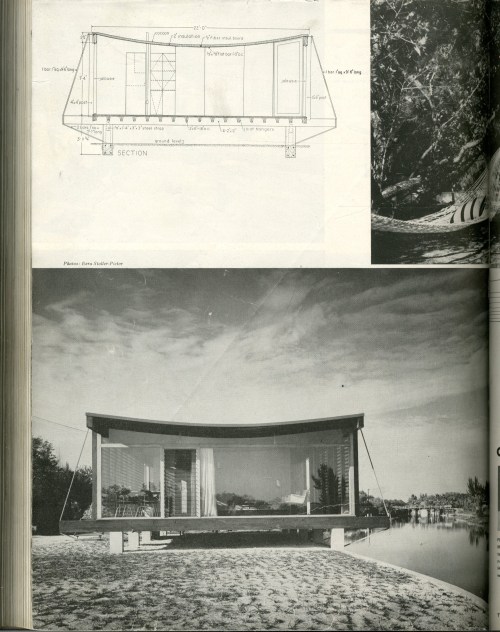

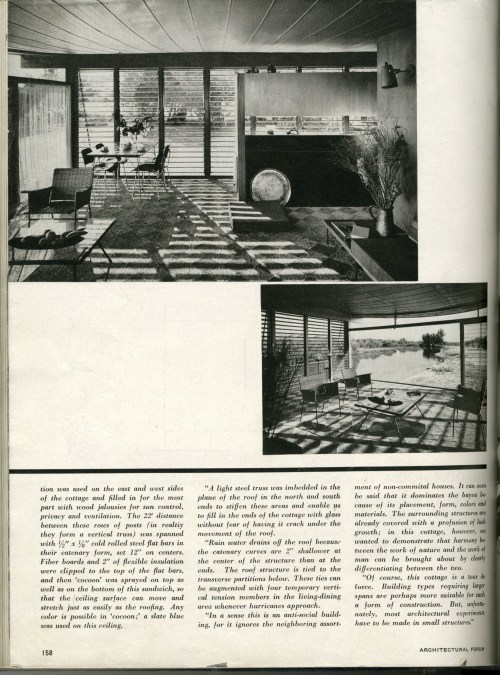

As the following period journal articles attest, Sarasota High School received a lot of attention from the architectural press and marked a turning point in Rudolph’s career.

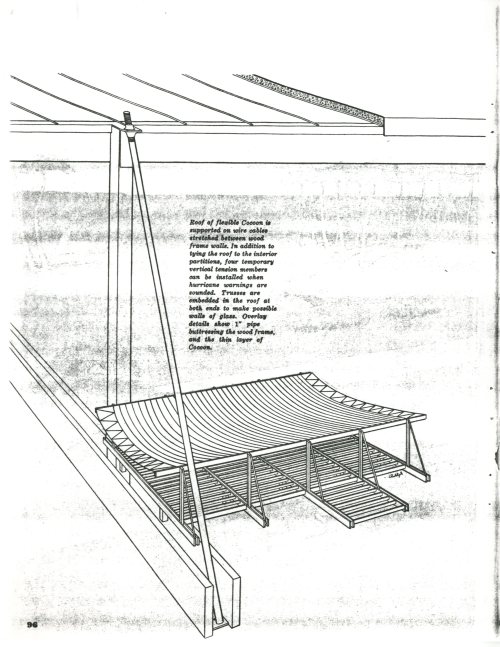

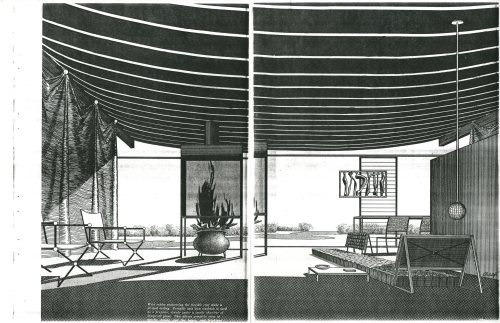

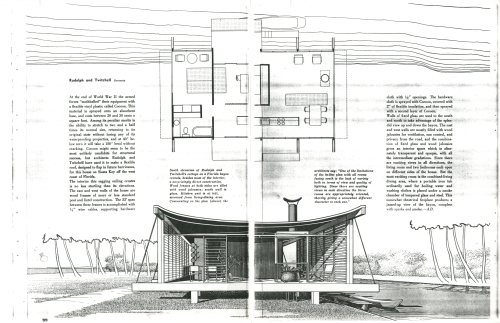

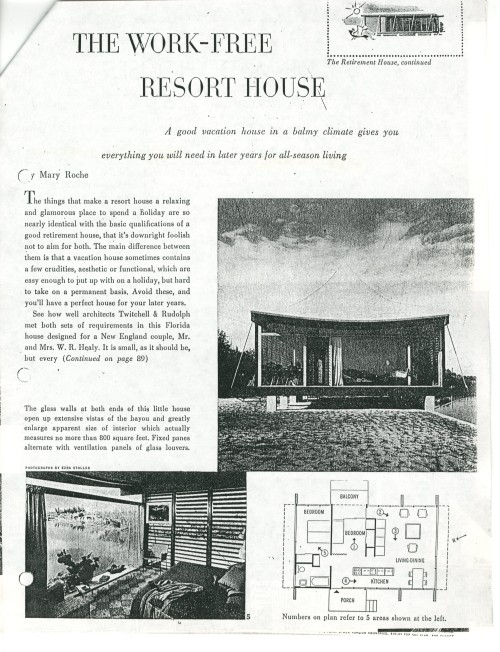

“Progressive Architecture” May 1960

“Architectural Forum” May 1959

“Architectural Forum” May 1960

Rudolph’s work at SHS received a different reaction from people who actually utilized it. Opened in 1960 on the heels of Riverview High School, the buildings were considered too progressive for Sarasotans and signaled the downfall of the Sarasota School of Architecture. Their steep price didn’t make the endeavors more digestible, nor did the the structural problems that arose shortly into the SHS classroom building’s tenure.

Then there was the structures’ lack of functionality. I attended Sarasota High and don’t remember the Rudolph-designed classroom building fondly. All concrete, it had slightly more charm than a parking garage, and sound seeped into classrooms from the hallway and neighboring rooms. And I never understood the reason for the breezeway’s roof cutout, which allowed rain to pour into an otherwise sheltered space. The large breezeway also makes it difficult to control access in and out of the school–not ideal in a post-Columbine world.

On March 14, I went to the Sarasota Architectural Foundation’s discussion “Sarasota High School: Paul Rudolph’s Legacy” at the Ringling College of Art and Design. With few exceptions, the event was attended by the foremost proponents of Sarasota School of Architecture preservation. Surprisingly, some of the school district’s facilities management personnel were seated near the front, a good sign that they were open to the preservationists’ ideas.

But I don’t think what they heard will change their minds. Instead of making a case for preservation to which everyone could relate, a majority of the panelists summoned Rudolph’s legacy. This may have played well to the–mostly–partisan audience, but I guarantee the facilities management people didn’t care. They think in terms of square footage and financial feasibility, not paying homage to dead architects. Same with the taxpayers and the SHS students and teachers who actually use the spaces.

But that’s not to say the Rudolph buildings at SHS should be demolished or drastically altered. For the Rudolph buildings to survive, they must be changed. No matter who designed them, they just don’t function well, and, it could be argued, they never did. No one may end up completely happy, but there are potential adaptive reuses that could appease preservationists, district officials, and the school’s students and staff. Perhaps the classroom addition could be a component of the nearby original Sarasota High School building, which is being rehabilitated into an art museum. One panelist at the SAF event, architect Joyce Owens, suggested the gym become the media center rather than enclose the breezeway. The school district doesn’t want that to happen for reasons unknown, but those are the kinds of ideas preservationists should rally behind.

Simply saying no to everything leads preservationists nowhere, but a reasonable plan that fits within its budget will be difficult for the school district to ignore.